A couple of posts ago, I promised details about how I constructed Chanel jacket #2.

Even though I was working on this project a year ago, it’s alllll coming back to me. The ill-fated muslins, the horrendous plaid matching, the pricked fingers and blood on my white lining, the furry fabric that felt like a shedding lapdog as I did hour after hour of hand sewing. No wonder it was sitting in my closet for a year!

Here’s the story: while in the thrall of creating Chanel jacket #1, which I made as a project for Susan Khalje’s “Couture Dress” course on craftsy.com, I started obsessively researching all things related to sewing a Chanel jacket. Looking at the Elliott Berman Textiles website one day, I noticed a listing for actual Chanel tweed fabric for $55 a yard. Not knowing at the time that that was a bargain for this type of fabric, I waited for a sale and got a couple of yards at 20% off.

Soon after, I completed Chanel jacket #1, then won a blue ribbon for it at the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Fair, which is a blood-sport crafting competition between rural crafters, hippy artsy folk, and overeducated gentleman/women farmers, with a few summer residents like me jumping in. Filled with hubris, and my $5 Fair winnings, I embarked on Chanel #2.

Embracing sewing has helped me get in touch with a scary competitive side of myself I didn’t know I had.

My plan was to use Vogue pattern 7975, (Vogue pattern 7975) which at that time was a favorite of Susan Khalje’s during her Chanel boot camps, though apparently she helps her students change the sleeve pattern into 3-part sleeves (Susan Khalje’s week-long Chanel Jacket class). So I started obsessing about the sleeve and decided to do a “frankenpattern” of that pattern with the sleeve from the Claire Shaeffer’s Vogue 8804 jacket pattern, which had just been released (Claire Shaeffer’s Chanel jacket pattern).

As I muslined 7579, which is a fairly conservative pattern with curving princess seams, I kept thinking, “I look lousy in princess seams,” and “this is too dowdy for me.” Undeterred and in denial, I finished the muslin and hated it. If you’re built like me, with boobs, a short waist, and hips, a fitted Chanel-style jacket is not your finest look to begin with, and it can easily turn you into a dumpy “pepper pot” (as the guys from Monty Python used to call themselves when they played middle-aged women in drag).

As I muslined 7579, which is a fairly conservative pattern with curving princess seams, I kept thinking, “I look lousy in princess seams,” and “this is too dowdy for me.” Undeterred and in denial, I finished the muslin and hated it. If you’re built like me, with boobs, a short waist, and hips, a fitted Chanel-style jacket is not your finest look to begin with, and it can easily turn you into a dumpy “pepper pot” (as the guys from Monty Python used to call themselves when they played middle-aged women in drag).

I hate the way I look in muslins, but I’m always glad I did them.

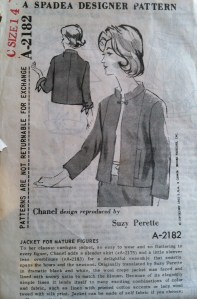

In the end I selected a Simplicity pattern (Simplicity 2154) with kimono sleeves and side panels, which I reasoned would be easier for plaid matching and construction. I had convinced myself that I could throw this jacket together. I have no idea why! I have seen photos of Chanel jackets using this cut, so it is an authentic look.

I muslined the Simplicity pattern and liked it a lot better–it had a much more retro 60s vibe, and it looked better on me. Also, I saw that I could create a vent on the top sleeve seam, which would save me the hassle of creating a three-part sleeve.

After taking about 2″ off the top shoulder/arm seam, raising the side panel to make the underarm higher, and cutting lengthwise rectangles at the cuff of the top sleeve seams to make the vent, the muslin was fitted and good to go.

I took apart the muslin and trimmed it to the stitching line to make the pattern pieces. I laid out the front pieces on one layer of fabric, side by side, so that the plaids would match up. Ditto for the back. The side pieces I thought would match pretty closely. I cut around the pieces, leaving a large seam allowance. At this point, you’re supposed to thread-trace (hand baste) around the pattern pieces to mark the seamline, but I think I used tracing paper instead. As I noted in the construction of Chanel #4, this is a bad idea because the tracing lines can permanently mark the fabric. But thread tracing is so boring!

Then the fun started. The fabric I selected has a subtle, very tricky, plaid repeat that is about 6″ long. So when you think you’ve got it lined up properly, you’re really about 2″ off. By the time I got into the serious matching and construction I got so obsessive that I spent hours trying to ensure that the large black thread was matching the other large black thread, and not the small black thread, which would completely throw off all of the fuchsia and grass green threads. It made me nuts.

For lining, I used a double silk georgette from Emma One Sock (emmaonesock.com), which, though lovely, I realized during construction was not all that sturdy for the amount of hand-work required. And even though I really liked the style of the kimono sleeves (because the bodice starts on the grain and then the sleeves dip down on the bias), when it came to attaching the bottom of the sleeve/bodice pieces to the two small side panels that go under the arms, it was such a pain. Such a pain! It requires a weird pivot on your machine that I botched and then ended up doing by hand. Set-in sleeves would have been a hundred times easier. But it was worth it, as it gives this jacket a non-traditional look.

For instructions, I used an old article by Susan Khalje from Threads Magazine (Threads Magazine article), outlining the steps she uses to make a traditional Chanel-style jacket, where, prior to construction, the lining pieces are quilted directly onto the exterior “fashion” fabric pieces. The exterior pieces are machined together, and then the interior seams allowances are finished by catch-stitching them down to keep them from rolling up. Finally, the lining seams are hand-sewn closed to cover the fashion-fabric seams.

So I machine-quilted the pieces of lining to the pieces of fashion fabric, using a walking foot. Then I attempted to put the exterior together, with the attached lining pieces flapping around the seams. No fun at all. I had convinced myself that I would close the lining seams by folding them over one another and machine top-stitching the whole thing, but it looked awful. So it was back to hand-stitching. Everything.

Here you can see my haphazard machine quilting, with the hand-stitched line where the lining was connected over the exterior seam. So much flippin’ hand sewing! If you look closely you can see a small dot of blood on the lining from when I pricked my finger. I can’t believe that some people do the quilting by hand, too.

I also watched a video from the Chanel atelier showing the construction of a modern “little black jacket” and saw that they were using fusibles to support the neckline, center front and sleeve cuffs. I decided that if it’s okay by Karl, it’s okay by me! (Video of the making of a Chanel “little black jacket”.)

What you’re looking at below, on the left, is the center front of the right bodice, with the edge reinforced by sewing on a piece of selvedge from some silk organza (I learned that trick from Susan Khalje’s Craftsy course) and stabilized with lightweight knit fusible. I did this around the neckline and cuffs as well. You can see that the lining was already quilted on so I have to fold it back to put on the fusible. The lining was constantly getting caught in the stitching during the exterior construction. Yiiii!

I turned in the center-front edge, hand catch-stitched it down, then turned under the lining and fell-stitched it down. Here’s the finished center front, after I had put on the chain and hooks and eyes.

I basically jerry-rigged some vents on the upper sleeves by cutting a rectangle, about 3″ long and 2″ wide, on the cuff end of the sleeve back piece. I turned the rectangle in by 1″ (self-facing it), catch-stitched it down, and then attached the lining.

At that point, nearing the freak-out zone, I remembered that I hadn’t done buttonholes in 30 years. We didn’t have a buttonholer when I was a kid, so I just went at them by hand. I like to think of the buttonholes on this jacket as “funky.” Note: you can avoid funky buttonholes and other pitfalls by consulting Claire Shaeffer’s book with DVD: The Couture Cardigan Jacket.

At that point, nearing the freak-out zone, I remembered that I hadn’t done buttonholes in 30 years. We didn’t have a buttonholer when I was a kid, so I just went at them by hand. I like to think of the buttonholes on this jacket as “funky.” Note: you can avoid funky buttonholes and other pitfalls by consulting Claire Shaeffer’s book with DVD: The Couture Cardigan Jacket.

Yes, that is a picture of Coco Chanel on those buttons. I bought a trashed Chanel blouse on Ebay, cut the buttons off and sewed them on the jacket. Now when I wear this jacket, stupid Coco’s always giving me that look.

Yes, that is a picture of Coco Chanel on those buttons. I bought a trashed Chanel blouse on Ebay, cut the buttons off and sewed them on the jacket. Now when I wear this jacket, stupid Coco’s always giving me that look.

I wanted to make the jacket look 60s, so rather than the jewel neck, I made the neckline more bateau. However, I had to close up the ends of the neckline, as the bateau shape made the front hang in a weird way. I still like it, though.

I found a roll of those vintage “La Cote d’Azur” clothing labels on etsy. Now they’re my “private label”.

For pockets, I was inspired by this 60s jacket:

but since I’m short-waisted, I didn’t want to do the upper set of pockets, which I assumed were for Coco’s ciggies anyway. More dastardly plaid-matching ensued while I created and lined two patch pockets and hand-sewed them on. (Basically cut a rectangle of fabric and one of lining, sew three sides right sides together, turn them right-side out, turn under the raw ends and hand-stitch, hand-sew on the trim, stick the pocket on the jacket and hand-stitch it on, repeat.)

Meanwhile, the exterior fabric was getting fuzzier and more played-out looking the more I stitched away, and the silk was getting tiny pulls all around the edge.

But as frustrating as it all was, I could see for myself why Chanel had added various design elements. The trim goes around the neck and center front to reinforce and stabilize that area without heavy tailoring. It keeps the neckline from flopping open, and it keeps the simple design from being too blocky and boring. Though I wasn’t using upper pockets, I could see how they would be useful on a princess-seamed jacket, to cover the place where the plaids don’t match at the bust point. The chain helps to keep the lightweight fabric hanging well so it won’t ride up, and the weight can counter-balance heavy buttons. The brilliant simplicity and wearability of this design has kept these jackets in vogue for more than 60 years.

I finally hand-sewed on the chain (time-consuming because you’ve got to get the needle around and through the metal loops) and hand-sewed on the trim and hooks and eyes. Then I put it in my closet until I recovered from the trauma ten months later.