In the past couple of years, I’ve become the proud owner of some pretty fab vintage designer patterns that I’m dying to make up. Here are a few examples:

A 1930’s Schiaparelli bias-cut dress pattern with label:

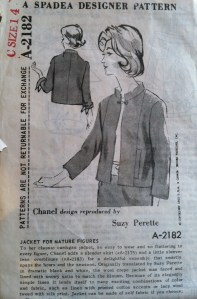

A 1962 Officially licensed Chanel Jacket pattern:

I did make that one up, and here’s the finished product: (And here are my posts about how I made it.)

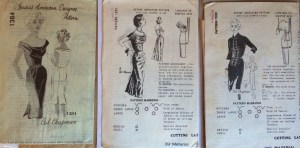

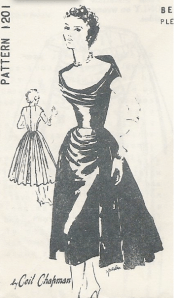

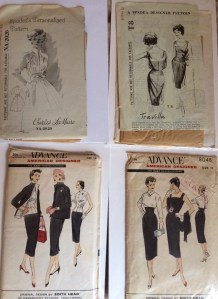

A number of Ceil Chapman patterns by Spadea:

Laura Mae from “Lilacs and Lace” has been blogging about making that “Skylark” style pattern in the middle, and it looks mighty tricky. (Lilacs and Lace blog)

Here’s an example of an original Ceil Chapman “Skylark” dress, with a narrow inner skirt and an over-skirt in the back:

No wonder Chapman was a favorite designer for stars like Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor. The dress played up the bust and made the wearer look like a beautiful bird. As an aside, here’s a link to the Hoagy Carmichael/Johnny Mercer tune that was popular in that era: “Skylark” sung by Ella Fitzgerald

And here’s the true Skylark dress pattern by Spadea, drafted from the dress above (I’d really like to find this one):

I’ve also been snapping up patterns designed by Claire McCardell, released by Spadea, McCalls, and Folkwear. Now I have more than a dozen.

Here’s a rare Charles James skirt pattern:

The inner workings of these skirt patterns show his genius for garment shaping through structure. There’s going to be a Charles James retrospective at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art starting this May 2014, which I’m now scheming to attend (waving my pattern…). (Charles James exhibit info)

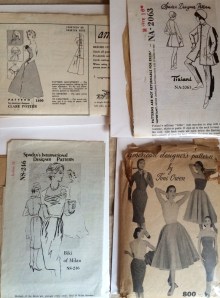

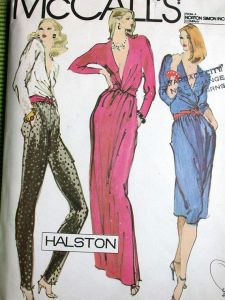

Not to mention several boxes of patterns by Pauline Trigere, YSL, Diane Von Furstenberg, Halston, Kenzo, Tiziani (by Lagerfeld) and a number of more obscure designers from the 50s and 60s such as Claire Potter, Jane Derby, Norman Hartnell (the Queen’s couturier), Tina Leser (the original Boho designer), Joset Walker, Jo Copeland, Vera Maxwell, Biki (friend and designer for Maria Callas), and Toni Owen:

Also patterns by Hollywood costumers such as Edith Head, Charles LeMaire, and William Travilla, who designed the iconic pleated dress Marilyn Monroe wore over the grate in “Seven Year Itch.”

I’ll be the first to admit that I have a pattern problem, and my husband will be the second to admit it.

Most of these patterns are way too small for me, and cut for the different body shapes that were popular at the time. For example, many of the 50s patterns assume that you’re wearing a girdle (which was basically Spanx crossed with a Michelin tire) and a bullet bra that raised the bust point by several inches. It was all about boobs and hips with a tiny short waist, like Elizabeth Taylor in the era.

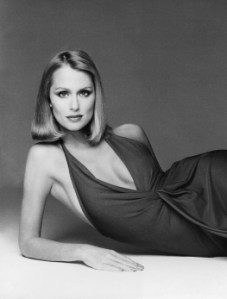

In contrast, the 70s DVF and Halston patterns basically assume that you might possibly be wearing slinky bikini underwear but probably not a bra (because you burned it at a feminist rally before you went to the disco), and the look was super-skinny with a small chest and hips, long torso and really long legs. Nobody worked out (it was pre-Jane Fonda aerobics) and a lot of women smoked and did coke, so the ideal was skin and bones. Here’s Lauren Hutton in that era:

In the picture, she’s wearing a dress by Halston that’s very similar to this late 70s pattern:

Of course a woman’s body can’t morph into new shapes to fit the fashions of the times, so we mainly just beat ourselves up over it.

I’ve gotten tired of starting from scratch in terms of fitting every time I take on a vintage pattern, particularly because my middle-aged body has fit issues of it’s own. So I’m going to see if making a “fitting shell” will help.

If you’re obsessively combing the internet for sewing fun facts (as I do to procrastinate about pinning and cutting fabric), you will see the terms “block,” “sloper” and even the haute couture “moulage” (Kenneth King’s Moulage book) bandied about to describe a basic pattern that is used by a designer to create new patterns.

I didn’t want to get my terminology wrong, so I consulted Kathleen Fasanella’s excellent blog about professional design and manufacturing, Fashion Incubator. There, I found out that patterns without seam allowances, called “slopers” or “blocks” in the sewing enthusiast world, are generally not used in the industry, and if you use those terms in a pro environment, you’ll be snickered at. She refers to the thing I want to make as a “fitting shell,” so that’s what I’m going to call it.

Basic fitting shell patterns have been available from pattern companies as far back as the 40s or 50s from what I’ve found online, and you can still buy them today. The idea behind these patterns is that if you make up the Vogue Patterns Fitting Shell and get it fitted closely to your body, then you can compare the fitting shell pattern pieces to any other Vogue pattern and easily adjust the fit.

I want to make myself a fitting shell so that I have a basic flat pattern pieces, fitted for me, to compare with the pattern pieces of the vintage patterns I own. That way, I can ballpark how much I need to increase the dimensions of the smaller pattern to fit my shoulders, bust, waist and hips.

Sounds great in theory, we’ll see how it goes in practice.

I looked at the modern fitting shells released by the Big 4 pattern companies, but nowadays modern patterns tend to have more ease built in, particularly in the armscye, and I want those high and tight vintage Chanel armholes.

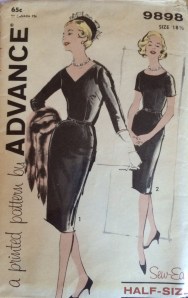

So I decided to buy some fitting shell patterns from the 50s and 60s, to see if they would work better. Here’s one from the late 60s, judging from the hairdo and squared-off pumps:

And here’s one that looks like late 50s:

This one in particular is for half-sizes, which nowadays I think would be referred to as “Petite Plus.” The “half-size” range is described in Connie Crawford’s current Grading Workbook as cut for a “more mature, short-waisted woman with a shorter, heavier body-type.” I can’t say I was terribly happy with that description, but at least now I know I have a “half-size” body with “full-size” legs.

And I was very excited to find out what “The Bishop Method” (written on the back of the pattern) might be.

I eagerly looked throughout the instructions but was bummed to discover that there was no mention of The Bishop Method inside.

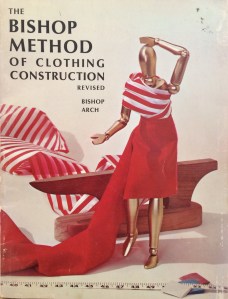

After a quick google, I found “Bishop Method” books all over the internet, and discovered that they were Home Ec manuals from the 50s and 60s. People were raving about them on Amazon! So of course I ordered one, because I need more sewing stuff.

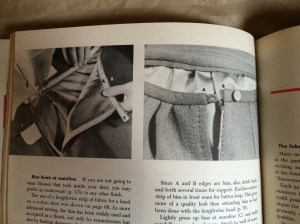

Holy smoke, The Bishop Method is the best flippin’ bible of vintage sewing techniques for the novice that I’ve ever seen! It takes you from square one (learning about the machine and making an apron)…

(that looks like the straight-stitch Singer 15 sewing machine I learned on.)

and goes all the way through making a tailored and lined suit with bound buttonholes and a hand-picked, lapped zipper.

It’s filled with clear, comprehensive instructions and a whole bunch of pictures. If vintage-style sewing with wovens is your thing, it’s worth getting a copy for your library.

There’s a lot of fitting info in The Bishop Method, and also in modern books like this:

(Threads “Fitting for Every Figure” book), which is extremely comprehensive and pretty text-heavy and labor-intensive, if that’s what you’re into, which I’m not.

With all of the schmancy sewing books in circulation right now, I’m kind of embarrassed to admit that my favorite book on basic fitting is this one by Nancy Zieman (of “Sewing with Nancy” fame), as it gets right to the point and illustrates the “pivot and slide” method of pattern fitting, which, though based on solid pattern-grading principles, is easy and fast and doesn’t require you to cut up your pattern.

She starts out by explaining the importance of finding a pattern that fits in the shoulders, and gives you the formula you need to figure out the proper size pattern to buy. (This helps if you use vintage patterns because even though the sizing varies, you can choose a pattern by bust measurement.) Then she shows you how to modify that pattern to fit the rest of your body by moving it around and tracing parts of it based on your measurements. There’s also specific fitting info, with illustrations, for dealing with issues such as broad shoulders, sway back, and bust adjustment.

So this is the method I’ve been using to fit paper pattern to muslins, and then I eyeball it from there. Since most commercial patterns are cut for someone with a “B” cup (I’m a “C”) and my waist and hips are a larger size than my shoulders, this method has worked well for me.

I recently read a review of Nancy’s life story, Seams Unlikely, on Gertie’s New Blog For Better Sewing (Review from Gertie’s New Blog…). The book talks about how Nancy embraced sewing in 4-H, and started her business from home back the bad old days when a woman was expected to get her husband to co-sign a business loan for her–even if he wasn’t involved in the business. It’s an inspiring story. Gretchen, thanks for giving us the heads up on that book.

Back to my fitting shell quest. In the end, I got lazy and decided to spring for a pattern drafted directly from my measurements, by String Codes. They take the five basic measurements you input and a create custom a fitting shell pattern for you.

Seemed easy enough, but when I placed the order and asked them to modify the bust measurement for a “C” cup, I was told that the patterns are only available as a “B” cup and that I would have to do a full bust adjustment myself. They did email me instructions with photos for an FBA, and it was a bit of a hassle, but not a deal-breaker. I’m going to make a muslin of the final pattern, and we’ll see how it fits. The pattern comes without seam allowances, so the exterior line is the seamline. You can see where I put in the bust adjustment below, following the directions from String Codes:

I ordered the “torso” pattern with a sleeve with a dart, since I often make jackets and tops, and also ordered the skirt pattern. I can overlap them if I’m making a dress.

As soon as I have it made up, I’ll do a little “show and tell” to let you know how it worked out.

And I’ll try to remember Nancy Zieman’s advice to avoid over-fitting, because “it can be exasperating and can take the joy out of sewing.” Amen, sister!

How’s your sewing going?

![10597356983_069525009b_z[1]](https://jetsetsewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/10597356983_069525009b_z1.jpg?w=300&h=300)

I love the Schiaparelli bias-cut dress. I think it needs to be digitized in the worst way. If you agree, let me know.

That sounds intriguing, Kathleen. I’m going to get in touch with you.

A whole 20 minutes have passed and still, no word from you. What’s taking so long? Don’t you know I want this *now*? 🙂

That’s hilarious. I just emailed you.

love this, Jules

Janet

Janet Eilber Artistic Director Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance

Thanks for stopping by, Janet Eilber, Artistic Director of Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, and thank you for making me those Barbie clothes when I was six. And teaching me to macrame that summer in the 70s when you came home from Juilliard.

(Okay readers, I’ll confess. She’s my sister.)

Wow, brought back memories, especially the Bishop Method. Here’s another one from Iowa Home Economics Assc from the early 60’s–Unit Method of Sewing, which features a fitting precursor to Nancy’s Pivot and Slide

Thanks for stopping by; I’m going to check that book out. I also have a vintage pattern-making book from Iowa State University that’s very useful: “Flat Pattern Methods” by Norma R. Hollen

Lovely to see your vintage pattern collection. I have an extensive (350+) vintage sewing patterns that I bought back in the early days of eBay. Have made a few and wear them whenever possible. I even collected Vogue Pattern Books from 40’s to 60’s. My vintage knitting collection is over the top as well. It would be great to somehow copy these patterns but battling with the pattern companies that still owns copyright is way above my head.

Love reading your blog and the inspiration that it provides.

My goodness, I covet your pattern collection! May I also recommend “Fashion Sewing the Bishop Method”. Great book!

Thanks so much Sandra! Sounds like you have a fantastic collection. One of my goals in collecting these designer patterns is to give these lost designs a new life when I can. The Spadea patterns in particular were drafted directly from designer retail garments.

If you or other readers have any of those Spadeas I’m always looking for, please get in touch with me!

Will look and photo but need some time as all my patterns are now locked away.

Thanks Sandra! No hurry, I have 8 gazillion others to work with…

Are you saying that the sloper or moulage is not used at all by pros, or just that it is called something else?

Also, that is for constructing and fitting a garment right, not developing a pattern. Unless all the patterns are made by draping and not the flat method. Fashion schools teach both.

Hi Lady ID! I’m glad Kathleen jumped in on that one because I was afraid I would have to answer it… Also, I was looking at Kenneth King’s website, and here’s his definition of a moulage, which appears to be for haute couture clients: “The moulage is the foundation of the couture pattern drafting system taught by the Ecole Guerre-Lavigne in Paris. This is a system of measuring the figure, calculating, and drafting a pattern that will fit the torso like a second skin, incorporating any of the infinite variations of shape the human figure can take.”

There’s certainly a lot of confusion about these terms online, so I’ll just stick with “fitting shell” since I’m working with commercial home-sewing patterns.

I was looking at your blog and saw all of those nice tanks you made. Have you thought about making some for the patternreview.com “Terrific Tanks” contest? Unfortunately, my tank-wearing days are over…

🙂 Thanks for clearing that up for me on the fitting shell. Re: tank tops, I did not know there was a contest but I will check it out. I have a few more tanks in the works thanks to LA weather 🙂

Oh and I have a Bishop book on my sewing wish list too. I have so many books on that list…I need a fourth bookshelf

Lady: we don’t use slopers or “moulage” (definitely a new fanci-fied term dusted off from someplace). If one uses the term “block” to mean a fitting shell, we don’t use those either. We do use blocks as we define them. Here’s a link that explains how we make patterns in real life.

http://www.fashion-incubator.com/archive/how-we-make-patterns-in-real-life/

Also, by necessity, schools must teach in a proscribed format but again, not how we do it in real life.

Thanks for helping out with that, Kathleen!

Ah, thanks Kathleen. I subscribe to your blog but haven’t read that far back. That was very timely.

I learned pattern drafting like seven years ago, and took a draping course last year. I love working with my sloper because of the math, walking seams, etc (weird I know) but as time passes, I tend to go to the patterns I’ve drafted before that I know work for me and modify those. It’s when I’m making a new silhouette that I go back to the sloper. You are right though, on the very rare occasion that I would modify a commercial pattern, I felt like I was being lazy. But the truth is that my understanding of drafting makes it easier to create a new pattern out of an existing one.

I’ve been meaning to make a block/shell/moulage because I’m getting a dress form and will need to pad it out. But I guess I’m getting to the same place as the person you referenced. Why reinvent the wheel, I might as well work with what has been refined over time. I’m still learning…:)

Me again:) I saw that you mentioned fitting shells may be used by custom clothiers. I remember reading something about Dior back in the day having custom mannequins for clients. That makes sense to me – you have to have a base point for the block right? Especially if you aren’t working on a collection.

Well, considering that haute couture Chanel suits can cost more than $50,000 today, I think they can spring for a custom dressform!

LOL. I would hope certainly hope so:) Just trying to clear up when they use a shell or not. Sounds like a “shell” is a basis for custom stuff, but collections and lines use blocks.

Fitting is in the air this week. I’ve been drafting a multisized shell/sloper with FBA/SBA instructions all week, and diving back into the library stacks to look at ‘vintage’ ones. I think a lot of the fit in older styles has to do with girdles and corseted brassieres (the ‘all in one’ Merry Widow) moving things to where style required them. Which means if you want that look, you need that underwear. If you aren’t going there, you need to redraft.

I agree, so I do take out the waist much of the time, and the bust darts can be a overly-pointy, too.

Thank goodness Spanx are easier to get in and out of (generally) than those old bullet-proof girdles mom used to hang on the shower curtain rod.

I recently posted about modern patterns that can be used to create a vintage look, and sometimes those can be easier to deal with than actual vintage patterns. Here’s the link: http://wp.me/p3ZjCS-6Z

I’ve also put vintage-style pattern suggestions on this Pinterest page: http://www.pinterest.com/juleseclectic/favorite-vintage-pattern-re-releases-and-vintage-s/

You are so industrious!

I have my mother’s old Bishop’s. She took a sewing class in the early 70s and that was the text the teacher at the community college used. I agree, it is a great resource.

That’s so funny about being industrious. It’s definitely the Midwestern girl in me; work a full day and then come home and crochet a few toilet paper roll covers (with dolls on top). The way the world’s going, I do think the crafters will inherit the earth.

You know what! I would suggest that you do a pattern making course or buy yourself a how to book and then make up your own blocks and then with your new found knowledge in pattern making ,use the vintage patterns and your blocks to design your own pattern . I really think that your creativity would be set to achieving great things!!

Thanks for that advice! Unfortunately I’m kind of old and lazy. I have read about making patternmaking blocks but kept putting off making them. There are courses on Craftsy that show you how to make them, and I was too lazy to do that! Here’s the link, and they call it both a moulage and a sloper: http://www.craftsy.com/class/patternmaking-basics-the-bodice-sloper/469?_ct=sbqii-jxucu-byij-ycw&_ctp=11&_egg=sekhiu_wqbbuho_20131031&_ege=469 . Right now I’m interested in bringing designer looks back to life, but you never know where it will lead…

Great post! I am so envious of your pattern collection especially the Chanel jacket! This post is very timely as I have been trying to sew my vintage patterns and find that it takes a long time to fit each one- a fitting shell sounds like the perfect solution!

Hi, and thanks for the nice words about the patterns. The Chanel pattern is great and authentic for that period. I’ll be using it again when I finally getting around to cutting Chanel jacket #5, AKA “The Kaiser.”

I’ll keep you posted on how the fitting shell goes. The tracing and fitting of these patterns is so labor-intensive that it really slows things down. It’s so nice when they’re finished, though!

You’ve got some really, terribly wonderful vintage patterns in your collection! It’s so lovely to know they’re in the hands of someone who can appreciate them. Your chanel with the mandarin styled collar was a show stopper. I’ve just started working on a new one for myself (albiet with a current Marfy pattern) and I’m currently just revelling in all the thread-basting.

I tried a vintage pattern once… a dress from the 60s. It was disaster from the get go, and I dumped it at muslin stage, unwilling to put in the time to force it to suit me, when I could be working on something more fitting (the path of least resistance). My sewing time is too precious to wrestle with something that required as much work as it did. Regardless – I’ll be reading along on how you grapple with using the shell to get the fit. Any particular pattern(s) that you’re going to focus on first?

Thanks so much. Vintage patterns are a challenge, and I prefer the designer patterns because, as frustrating as they are, you do learn a lot about the thinking that went into the design. I have a Claire McCardell “popover” dress and that 30s Schiaparelli dress on my list to get into the wearable muslin stage for summer, and another French jacket from that Chanel pattern in the fall.

The fitting shell from stringcodes.com is almost finished, and has fit well with only a few modifications, which I expected. I’ve already used the skirt shell on the Charles James skirt, and it was very helpful!